Computer chips, also known as semiconductors, can be found in millions of products.

From smartphones and games consoles to laptops and washing machines, they all rely on chips to work.

And this holds true for cars too.

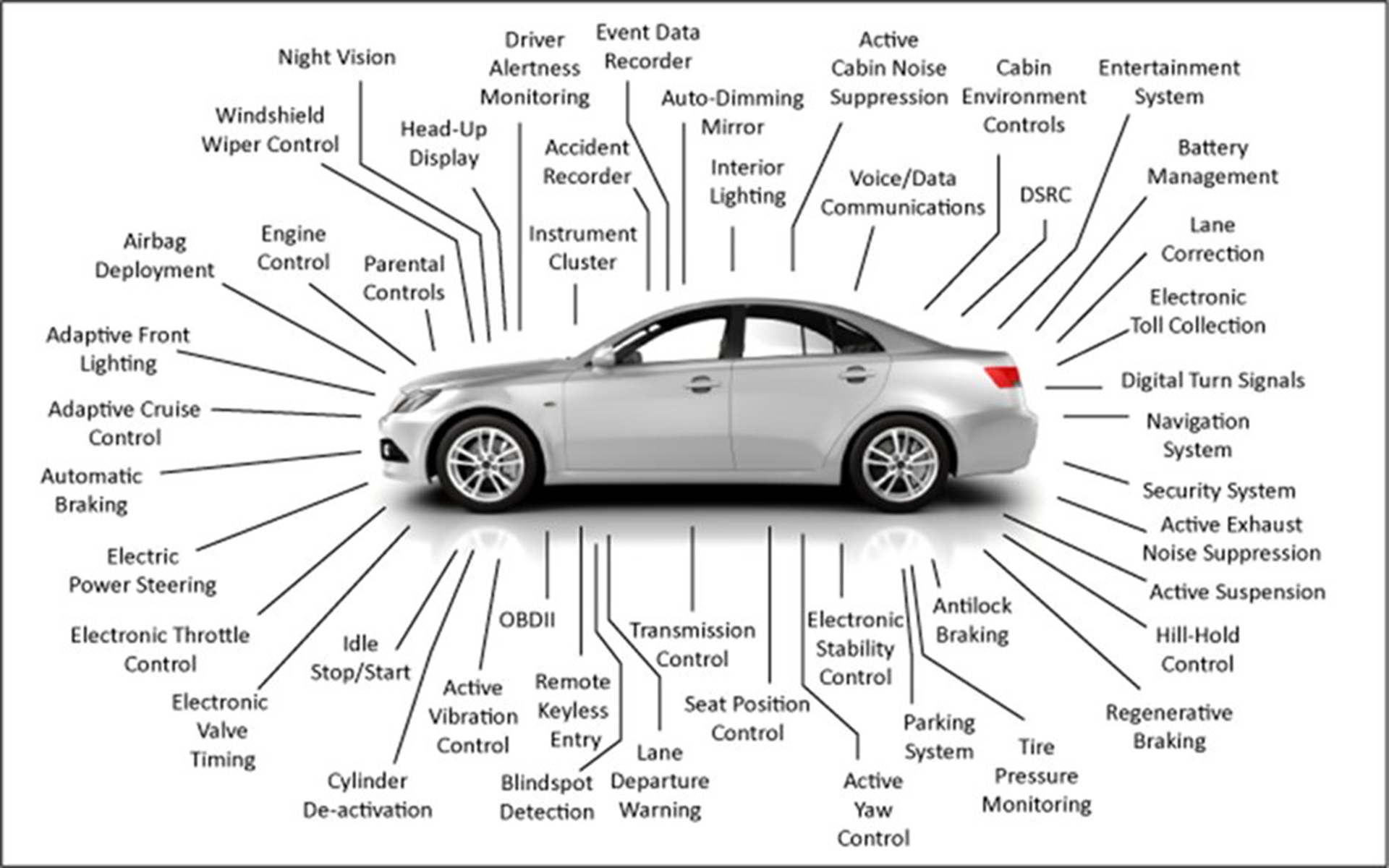

Lift the lid on a modern car and you will find it is packed with anything between 1,500 to 3,000 chips.

They are critical components used in areas such as entertainment systems, navigation, emergency braking, airbags, and emissions control.

Why is there a global shortage of semiconductors?

“Essentially, supply capacity has not kept up with demand,” says Morris Cohen, a professor emeritus at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania who specialises in manufacturing and logistics.

“With the pandemic, the big question is, are we consuming more chips? And the answer is yes, we are. People are buying more computers, more cellphones, they are buying all kinds of electronic devices.”

One of the big problems for the chip suppliers is that they cannot respond to this increased demand by simply switching on a new factory or ramping up production of these chips overnight, a spokesperson from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) told WhichEV.

Chips are complex products. The capital cost to set up a factory where they make the chips is “multiple billions”, says Professor Cohen.

“It takes at least a year to build a factory and it takes another year to essentially tune the manufacturing process so that the yield, the fraction which comes out of it that is usable, is at an acceptable level.”

Another issue compounding this is that computer chips used in cars are not substitutable, even for the same function.

Professor Cohen said: “If you have an entertainment system for Ford and compare that to the one in General Motors, they are very similar chips, but they are not the same, you can’t plug one in and substitute it for the other. That’s not true for computers by the way. Computers have standardised components.”

The result is that popular products are being left in short supply and chip suppliers have been forced to go on allocation, also known as rationing.

Automakers are not being given priority…

The chip suppliers are favouring the larger companies that make computers and smartphones over automakers.

“The market is bigger for those, and the margins are higher,” explains Professor Cohen.

“The chips that go into computers are the most advanced chips that can be made whereas the chips in EVs are not the most advanced, so they don’t get as high a margin. This means the rational thing to do is to not give priority to carmakers.”

This has forced many established automakers like Ford Motor and General Motors to close one factory after another.

However, one manufacturer that seems to have been less affected by the semiconductor crisis is Tesla.

Tesla’s vehicle deliveries in 2021 increased by 87.4% compared to 2020, according to the SMMT. The American company set a new record for fourth quarter sales and in September 2021, the Tesla Model 3 became the bestselling car across all fuel types in Europe, and was the bestselling car in the UK in December 2021 too.

How is Tesla avoiding the chip shortage?

While Tesla has given scarce details about how it has left its competitors in the dust over the past year, it is becoming clear that the company’s success during the pandemic is down to its technological knowhow and superior command of its own supply chain.

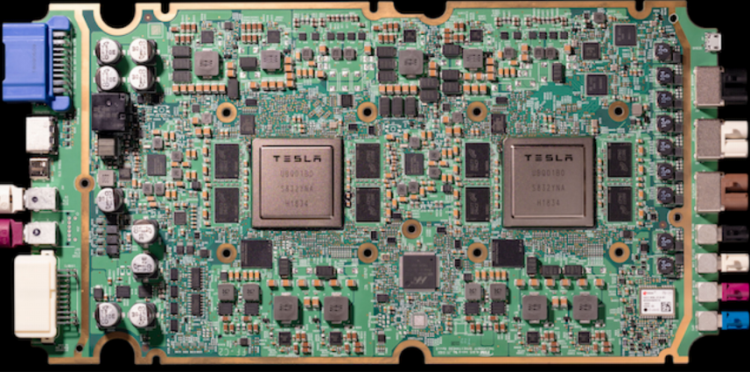

When Tesla could not obtain the hard-to-find chips it needed, it took what available chips there were and had its in-house coders rewrite the software that operated them to fit its needs. Other larger car manufacturers did not have the computing expertise to do this, relying instead on outside suppliers to write software for them.

“Tesla controlled its destiny because it controlled the software that went into the electronics that went into the car,” says Professor Cohen.

When Reuters spoke to a Tesla insider who helps engineer the firm’s chips, they said: “We design circuit boards by ourselves, which allow us to modify their design quickly to accommodate alternative chips like powerchips.”

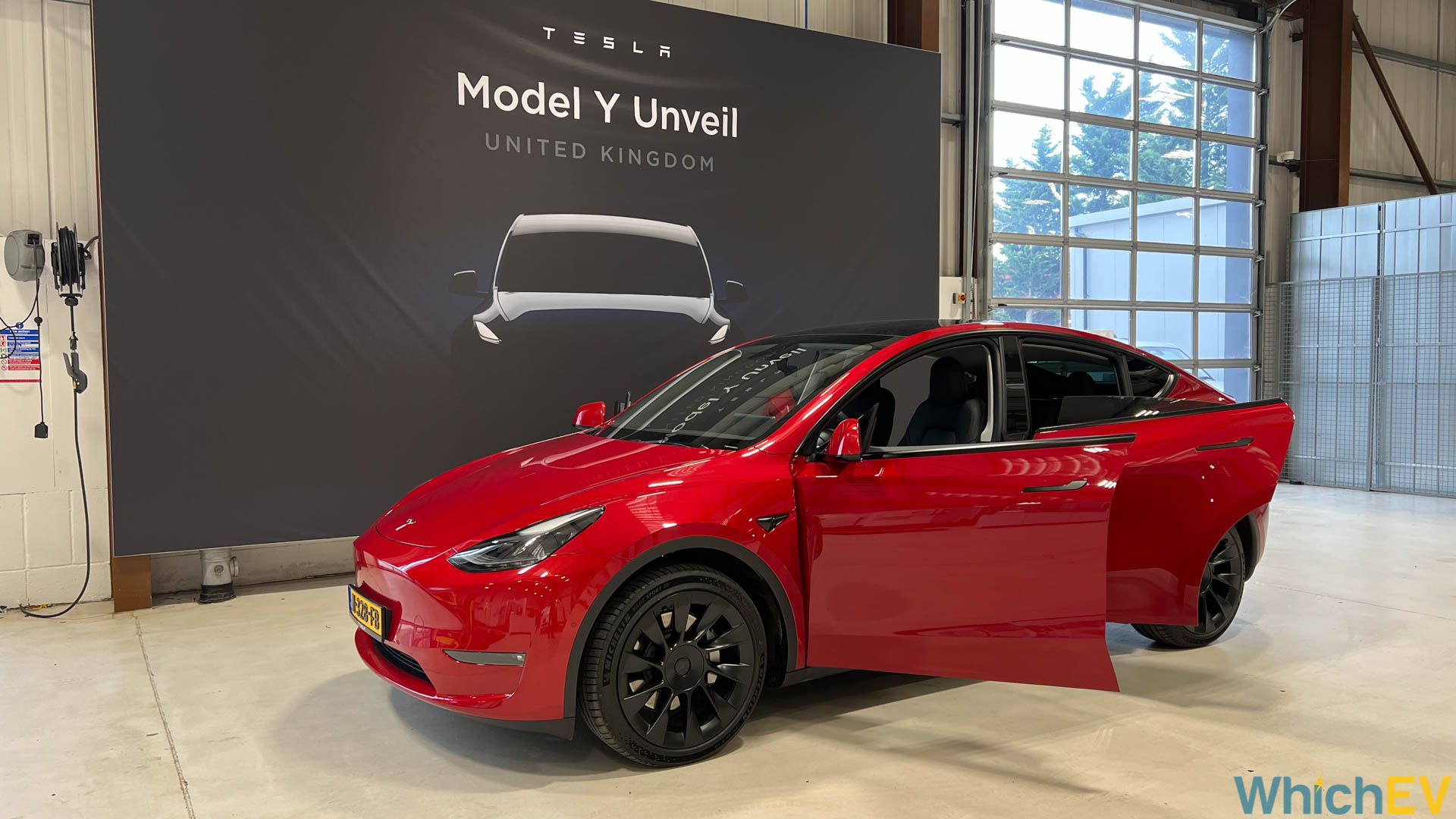

What makes Tesla such an agile business is also partly to do with its origins. Born in Silicon Valley, it is more like an electronics manufacturer than an automobile manufacturer. Jump inside a Tesla Model 3 and you will see that cars are becoming increasingly digitised, defined by their software and gadgets as much as their engines.

“I happen to own a Tesla Model 3 and it’s actually more like a computer, it is not the same driving experience as say a BMW,” says Professor Cohen.

“It’s a computer that happens to be on wheels.”

It is important to note too that Tesla is a much smaller company than say Toyota or Volkswagen, which have been known to pump out more than 10 million vehicles in a year.

Not only is Tesla’s supply chain naturally smaller, but it also has a modest line-up making the manufacturing process more streamlined.

Nearly all of Tesla’s deliveries in 2021 came from its Model 3 and increasingly popular Model Y SUV, while its Model S and Model X represented just 3% of sales overall.

Added to this is that compared to other automakers, Tesla uses fewer chips in its cars in general. Analysts say this is because the company controls systems such as battery cooling and autonomous driving from fewer centralised computers.

Companies like Mercedes-Benz and Ford are now realising that they need to follow in Tesla’s footsteps by hiring programmers so that they can start designing their own chips in-house.

For instance, Mercedes is planning on using fewer specialised chips in future models, opting for standardised semiconductors so that it can write its own software, according to Markus Schäfer, a member of Mercedes’ management board overseeing procurement and supplier quality.

Looking forward, the outlook for traditional car makers is expected to pick up as the chip shortage eases and manufacturers learn to adapt. This means Tesla is likely to face its stiffest competition yet in 2022.

Discussion about this post